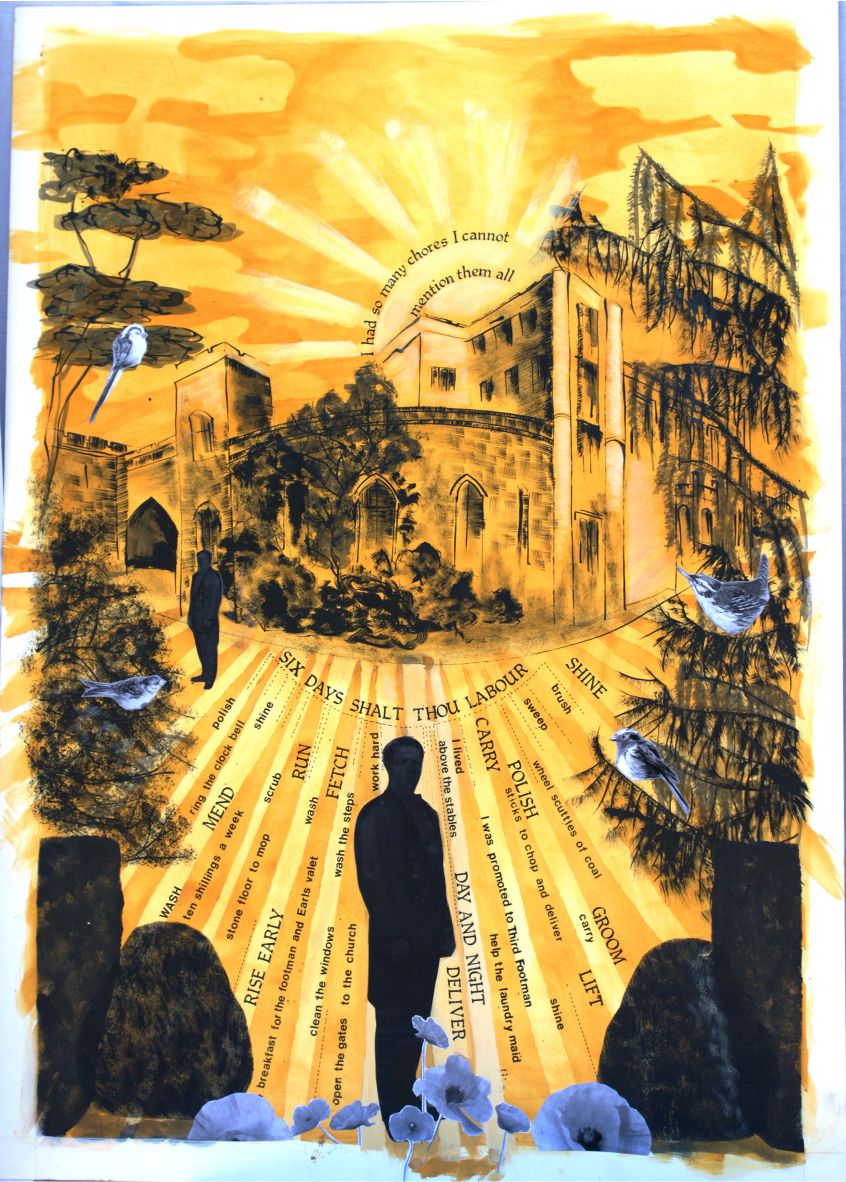

Painting 1. Charley’s Early Years

Charley had a very happy childhood and recounts many of his adventures in his book.

“As these happenings of childhood return to me it is as though I was reliving those happy years. There was the time when the Earl of Harrington’s hounds met at the Golden Gates, always about playtime which as I have mentioned earlier, was at 10.30am.Bass Kerry and I knew of the Meet so we awaited our opportunity and just before the children went back to school, off we went to the Meet. We kept well out of the way of anyone being sent from the school to call us back. We waited until the huntsman, then a Mr Earp, rode through the gates leading his pack of hounds into the castle grounds. The hunt followers were not allowed in these grounds, but waited until they and we boys heard the baying of the hounds and the huntsman’s horn, that indicated that the hounds had “scented a fox” and were giving chase.”

---------- “Nowadays there is quite a lobby against fox hunting and it is considered a very cruel sport, but in those days it was considered a very exciting sport indeed. Bass and I returned to school, managing to sneak into lines and mix with the other boys and girls after the afternoon playtime.”

Charley and Bass were caned by the schoolmaster Mr Creighton for this but strangely Charley’s father did not. He often wondered why.

Painting 2. Growing up

Charley left school at the age of thirteen and went to work for his father who was a stone mason on the estate. During quiet times they went to work on the farms. At the age of sixteen he got a job as “odd-man-cum-third footman at the castle”.

“I lived in a room over the stables, sharing with the second footman. I was called up about 6am by the night watchman, Mr Canty, my first task being to wheel scuttles of coal from a forty ton heap into the castle, the coal for the downstairs rooms into a bunker and coal for the upstairs rooms I had to take up on a hydraulic lift. “ ------------

Charley also had to chop and deliver wood, and mop the stone floor where his barrow wheels had been.

“Then I had to rush to have a wash and brush up ready to lay breakfast for the footmen and the Earl’s valet and at 7.55 dash to the clock tower where, after the clock struck 8am, I rang the clock bell .”----

The bell called all workers on the estate to their tasks and he also rang it at 1pm and 2pm. On Tuesday mornings after a 5.30am start he helped the laundry maid turn the linen press by handle..

-------------“I had so many chores I cannot mention them all. I did not get a break until his Lordship and her Ladyship dined at 8pm.”--------------

Charley occasionally acted as valet to both the Earl and his male guests.

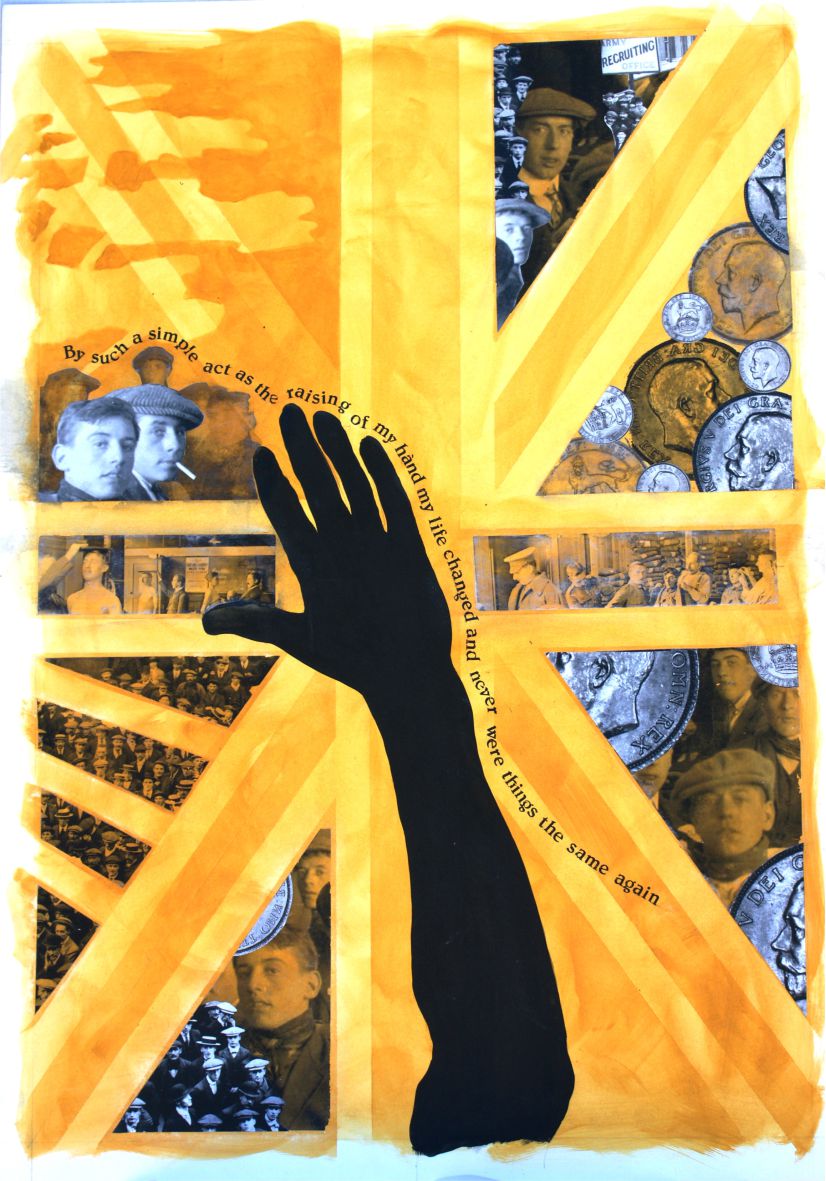

Painting 3. Volunteering For War

“The Earl called a meeting in Elvaston school of all the young men in the villages and there he put out a call for volunteers for his Majesty’s forces. The Earl continued, “You all know how vital it is that all young men of military age should seriously consider the defence of their homes, families and country. Now I call on you young men for volunteers”. After a pause up went my hand and also those of Jack Billings and Frank Waldron. The Earl then said, “One of my own servants is the first to volunteer.” By such a simple gesture as the raising of my hand my life changed and never were things the same again. This was the end of an era.

I was told to give my name to the Parish Clerk, then present, and this I did. Within two weeks I was notified to report to the recruiting officer at “The Spot” Derby, and after signing on I was given the King’s Shilling and told to return home to await my calling up papers.”

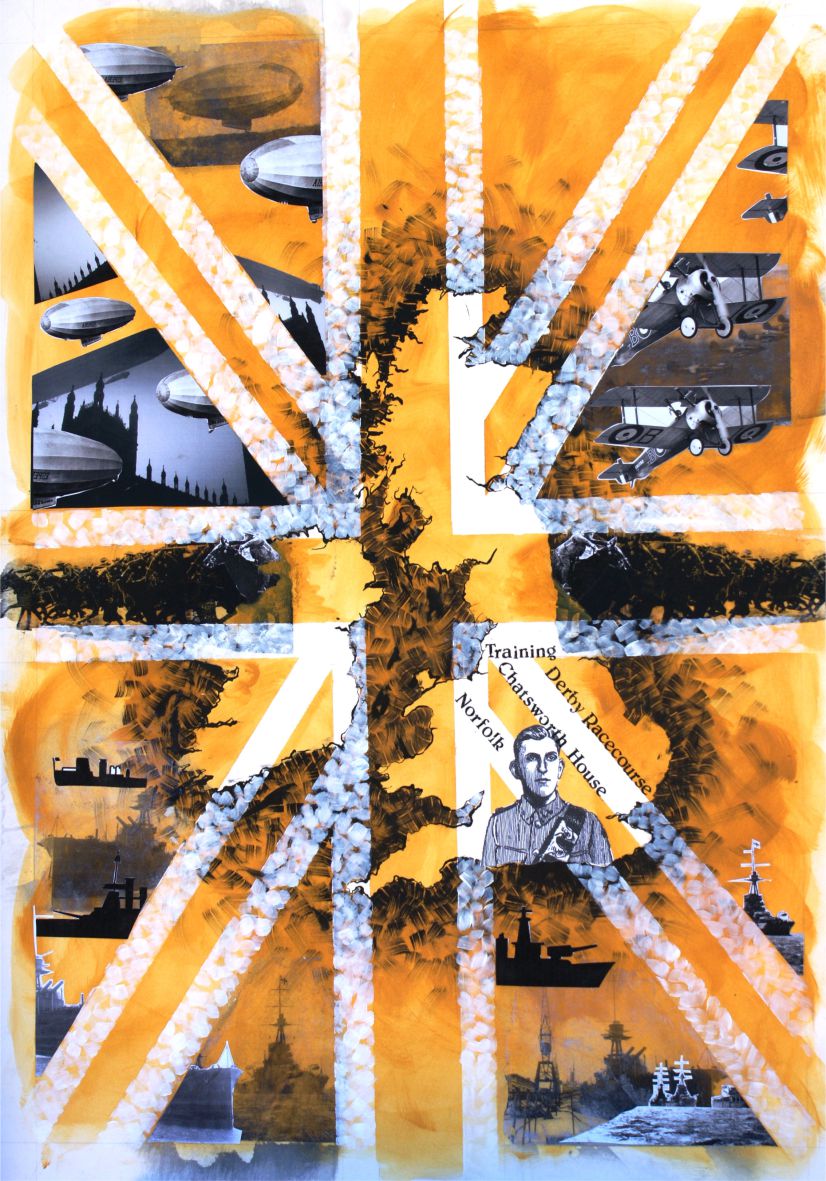

Painting 4. Derby, Norfolk and Egypt

Charley’s army number was 1995 and he joined the second line of the Derbyshire Yeomanry with his brother Harry, Alf Sturgess, Dan Canty, Alf Hapsley and Frank Waldron.

“We were fitted out with khaki and cavalry equipment and before long we commenced our training on Derby race course.”

Here they were taught to ride before moving to Chatsworth for more training. At the end of November 1914 Charley, Alf Sturgess and Dan Canty volunteered to join the first line in Norfolk. In April 1915 the whole regiment was ordered overseas to Egypt.

“On arrival at Alexandria we were linked up with our horses --. We rode to a newly made camp called Sidi Bish. The heat was terrific, there was little water and much too much sand.”

“Life went on sweetly until early August we heard rumours about the bad time the troops were having in Gallipoli and it was not long before this became a reality to us.”

They embarked on the troopship SS Haverford. During the voyage they were given talks about what to expect on landing and that “Some of us may not come back”

Click on Painting 4 to see it in higher resolution…

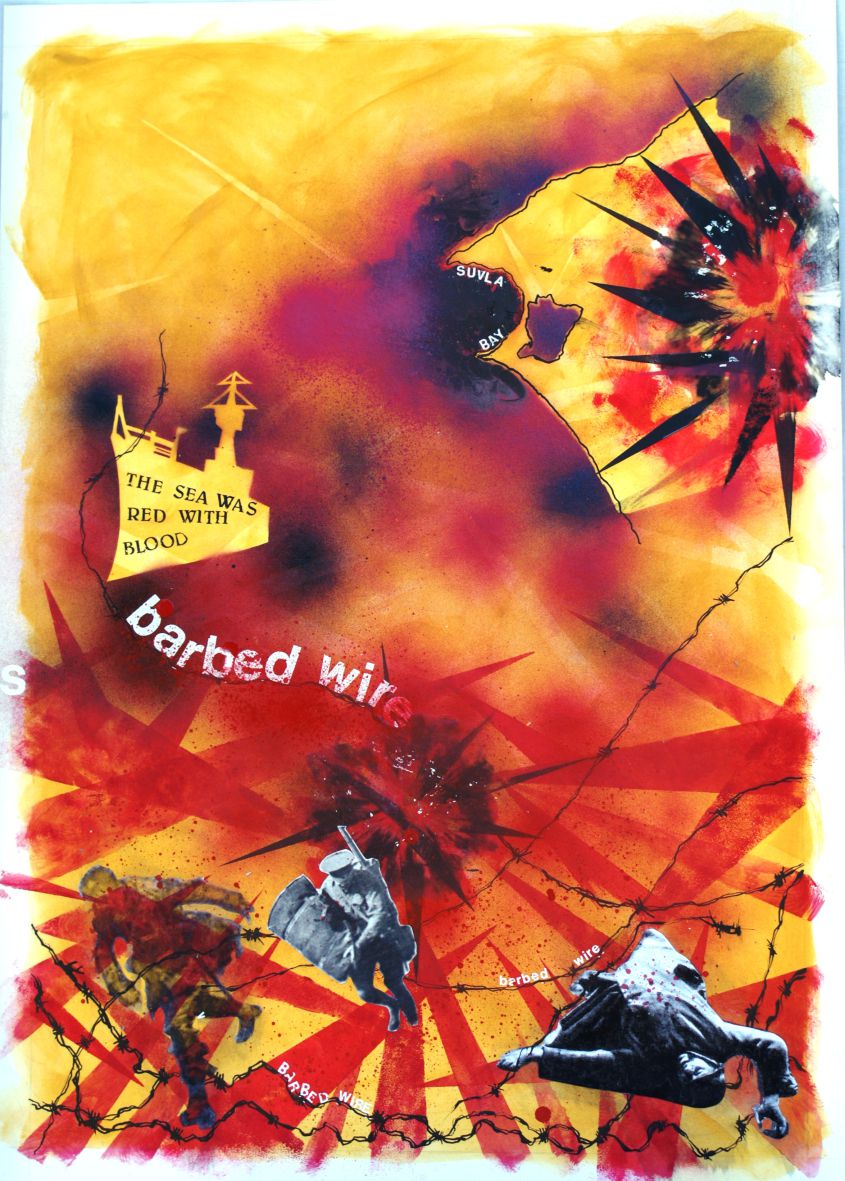

Painting 5. Suvla Bay

“Entering Suvla Bay through the Dardanelles, we approached the fighting zone. The Haverford dropped anchor away off shore but well in range of the enemy’s big guns. Shells were bursting all around us and our own navy guns were replying in like manner. Navy picket boats drew alongside and soon filled up with troops and made for the shore. Enemy shells were dropping on the sea all around us and it was dreadful to see some of those small boats catching the brunt of the enemy’s wrath. When our picket boats were close to the shore - orders were given to jump into the sea and wade ashore. -------“

“Most of us made it but not all. Many of the lads became entangled in the barbed wire which the Turks had laid underwater and the sea was red with blood.”

Painting 6. The Trenches

The regiment assembled on a flat plain named Salt Lake, it’s objective being Chocolate Hill, about two miles distant. When they were on the move towards this hill the enemy opened fire with everything they had. The ships responded with a very heavy bombardment.

“The enemy, however, had the advantage -- as he was entrenched in the mountainous hills opposite and we were at his mercy. The only encouraging sound was that of our own naval guns behind us pounding the enemy’s hill positions. I shall never forget that first baptism of fire and the resultant carnage. Was I scared? Of course I was.”

The regiment was then ordered to dig in. This was practically impossible as the terrain was rock hard. They moved towards Chocolate Hill under cover of darkness and all they could hear were the calls for Stretcher Bearers.

“At this stage in the hostilities we were almost at starvation point as rations and water were scarce --- however we managed to survive, but only just.”

The war dragged on with small arms fire from both sides with soldiers popping up over the trench to shoot.

When you appeared over the trench you were a prime target ---- to minimise this you could hear a non-com shouting, “Keep your bloody heads down” Some didn’t and paid the penalty.”

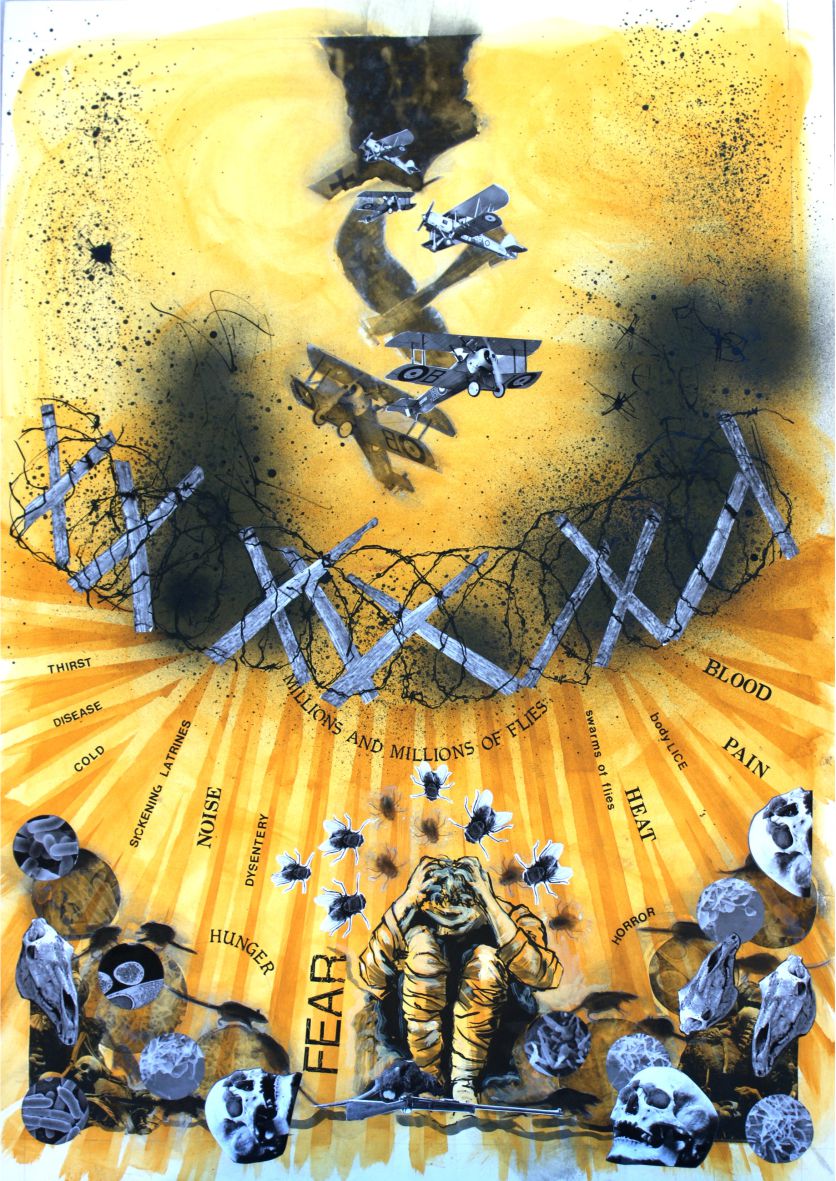

Painting 7. Flies, Germs & Sickness

The fighting dragged on with many deaths and much sickness. Charley doesn’t say much about the conditions but other accounts tell of the dirt and the flies which swarmed and landed everywhere they could in inconceivable numbers on the men. The men suffered badly from sickness and in October Charley succumbed to dysentery.

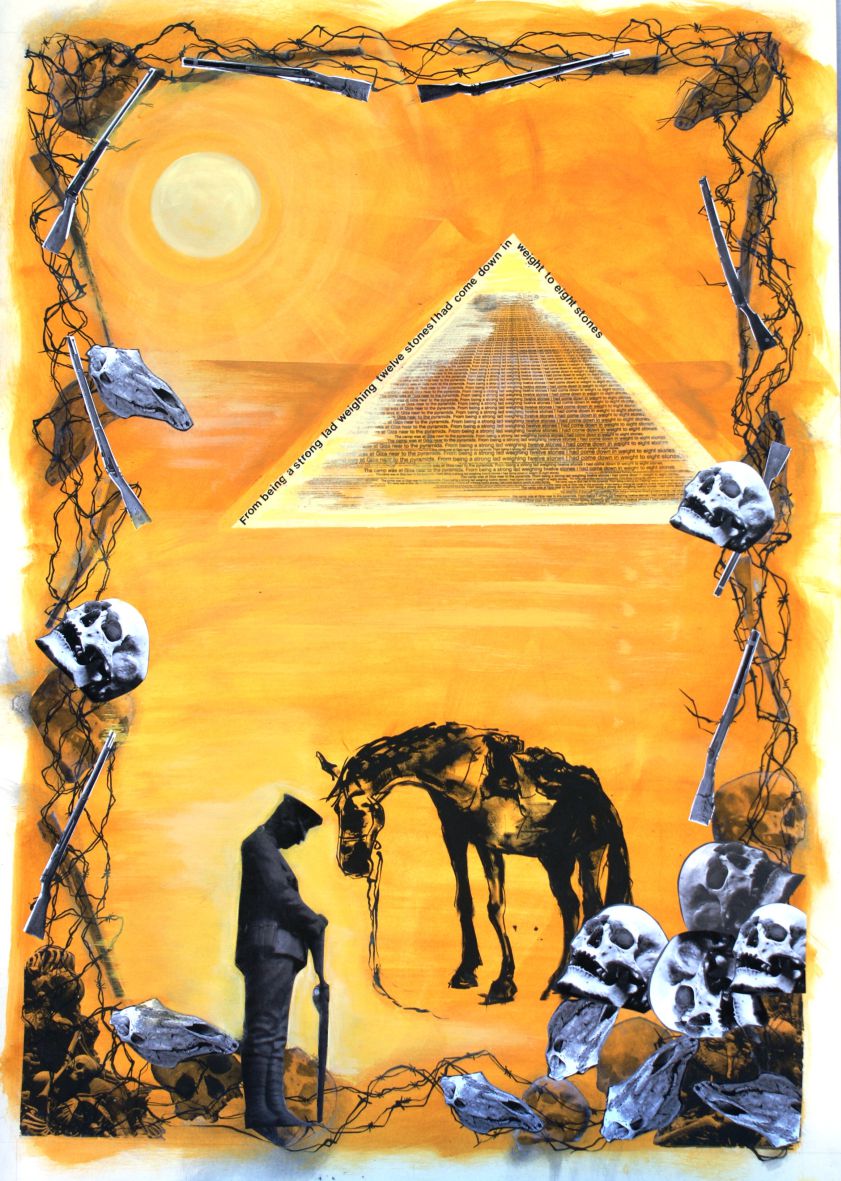

“I was attending daily sick parades until one night I passed out, but for how long I have no idea because when I came to my senses I found myself in a military hospital in Alexandria. After about a month I was transferred to a convalescent camp nearby, and then in December I was passed fit and returned to my regiment The Derbyshire Yeomanry.”

When he rejoined his old troop he found that the infantry equipment had been discarded and they were once again a cavalry unit.

“The camp was at Giza near to the Pyramids. It took me some time to get re accustomed to the saddle as from being a strong lad weighing twelve stones I had come down in weight to eight stones. I could mount alright but once in the saddle it felt as though my arse bones were pushing my neck out of joint. However I mastered this discomfiture in time”.

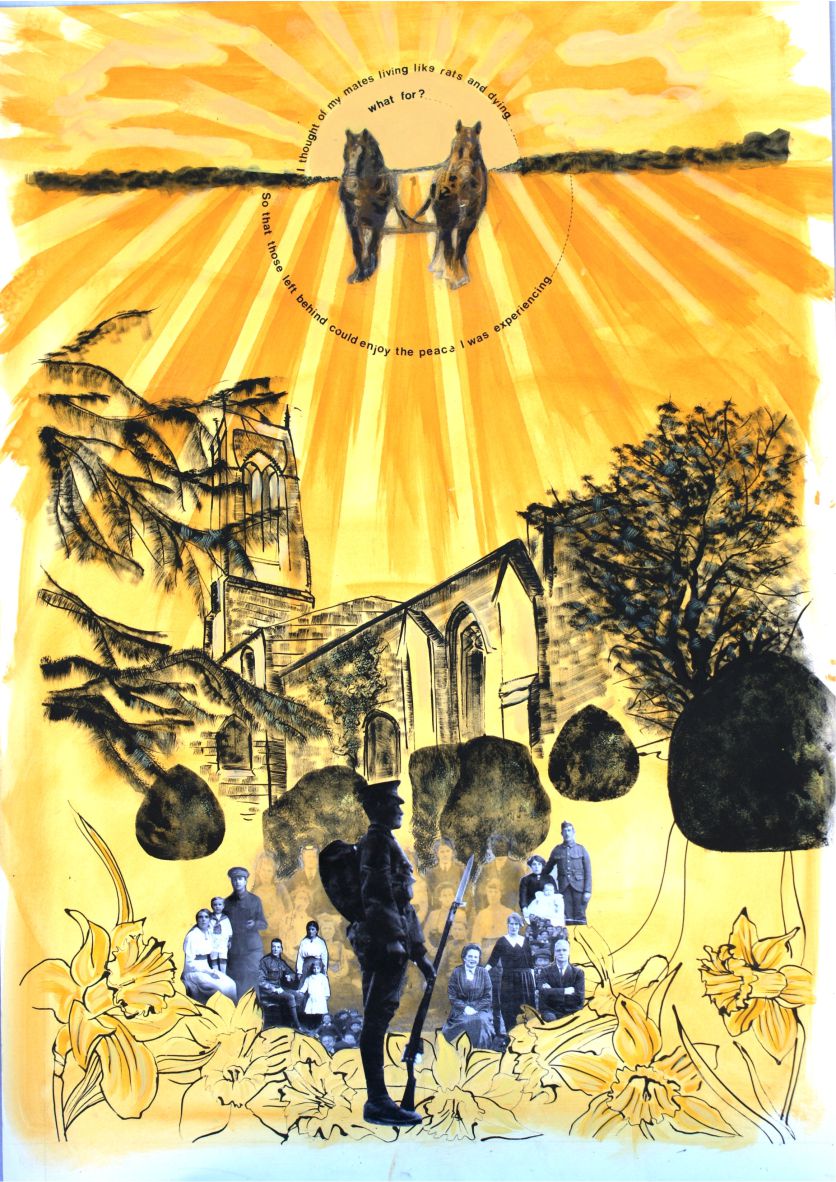

Painting 8. Home Leave and Malaria

Charley went home on leave. April 1917

“---- Derby where I was met at the station by my girlfriend, Frances, and my Aunt Lottie Rice. What a happy reunion I had with my parents, sisters and brother Humphrey. My other three brothers were already with the fighting forces in France.”

On Easter Sunday we all went to Elvaston church. It was a beautiful Spring day, and the churchyard was bright with daffodils. I remember pausing at the gate taking in this typically English scene, surrounded by friends and with the church bells ringing. I thought of my mates living like rats and dying – what for? – so that those left behind, and those to come after, could enjoy the peace I was experiencing.”

Four days before Charley was due to return to duty he developed a very bad attack of malaria. His doctor informed his regiment and he was granted a further two weeks leave to recover.

Painting 9. Wounds and Crippen

Soon after this Charley became extremely ill with a shell splinter in his leg. He was sent to Kas-el-Neal military hospital where he was operated on. He was lucky not to have lost his leg. The hospital authorities contacted his parents who were later reassured that his condition was “Satisfactory”.

Having recovered from his wound Charley was to rejoin his regiment in Salonica. Replacements were arriving from England to supplement the regimental losses and they travelled by troopship from Alexandria to Salonica in January 1916. Charley joined his old Number One Troop A Squadron.

He was given the responsibility of caring for Major Guy Winterbottom’s two horses, Dream (the Major’s) and Crippen who had the reputation for biting and kicking. But Charley and Crippen got on very well went through the rest of the war together.

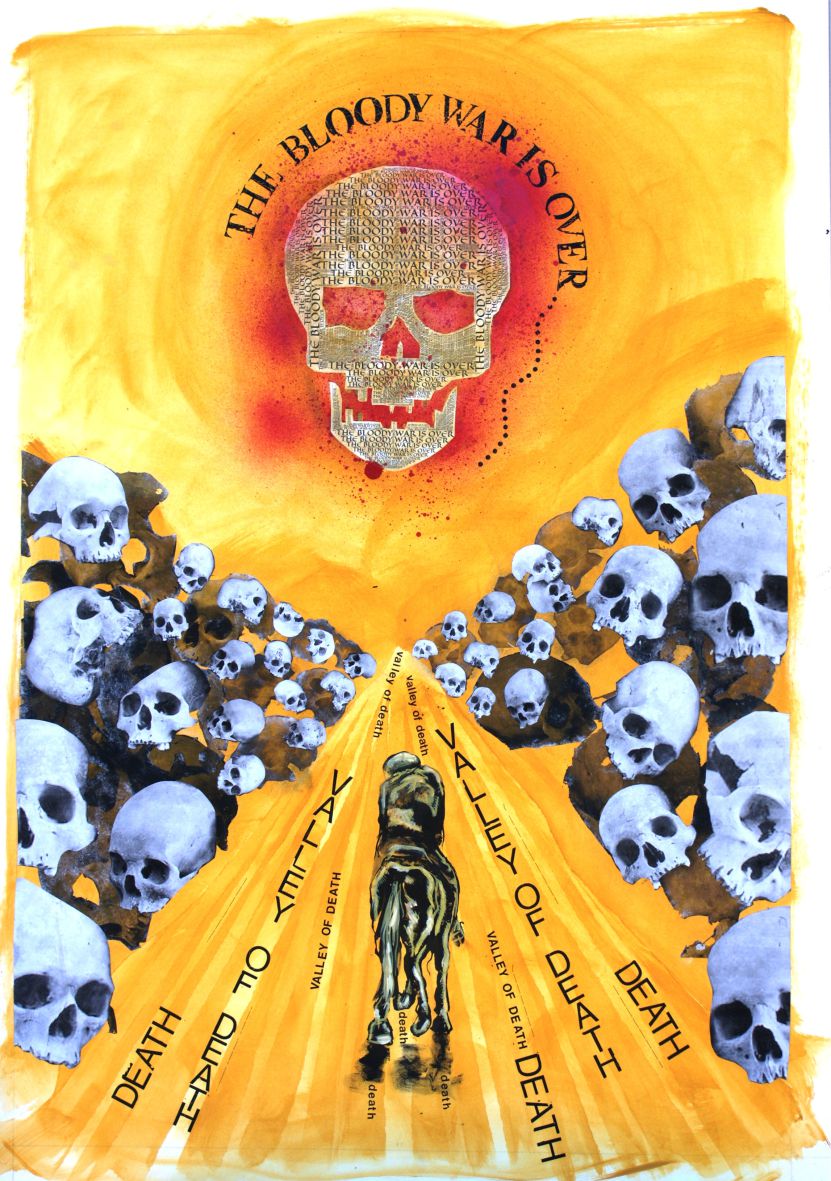

Painting 10. The Valley of Death

Hostilities were quiet for a couple of months then, in late June 1917 the squadron moved to a new camp called Kopaki. For months they remained in this camp, keeping up penetrating patrols.

At the beginning of September 1918 they moved to a camp at Killender, near the mountainous Gran Gorrans region. An assault by a Scottish brigade dislodged the Bulgar troops and they were on the run.

“The Bulgar on his retreat had been trapped in a valley which I named the Valley of Death, as I never saw, and trust never to see again so many dead Bulgarian soldiers, dead horses, broken vehicles, cannon and the like. The stench was unbearable. Our horses had much difficulty in picking their way without treading on a corpse.”

The following morning the Bulgar forces surrendered to Lieutenant Lowe of Number three troop A Squadron. The beginning of the end of the First World War.

After a brief rest they moved through the hills in heavy rain. The troops were riddled with malaria and for five days had nothing to eat as the supplies transport had been held up. When it arrived the driver of the first cart “---was shouting for all to hear “The bloody war is over! The bloody war is over!” What a birthday present it was for me as, yes, it was my birthday, 11th November 1918”.

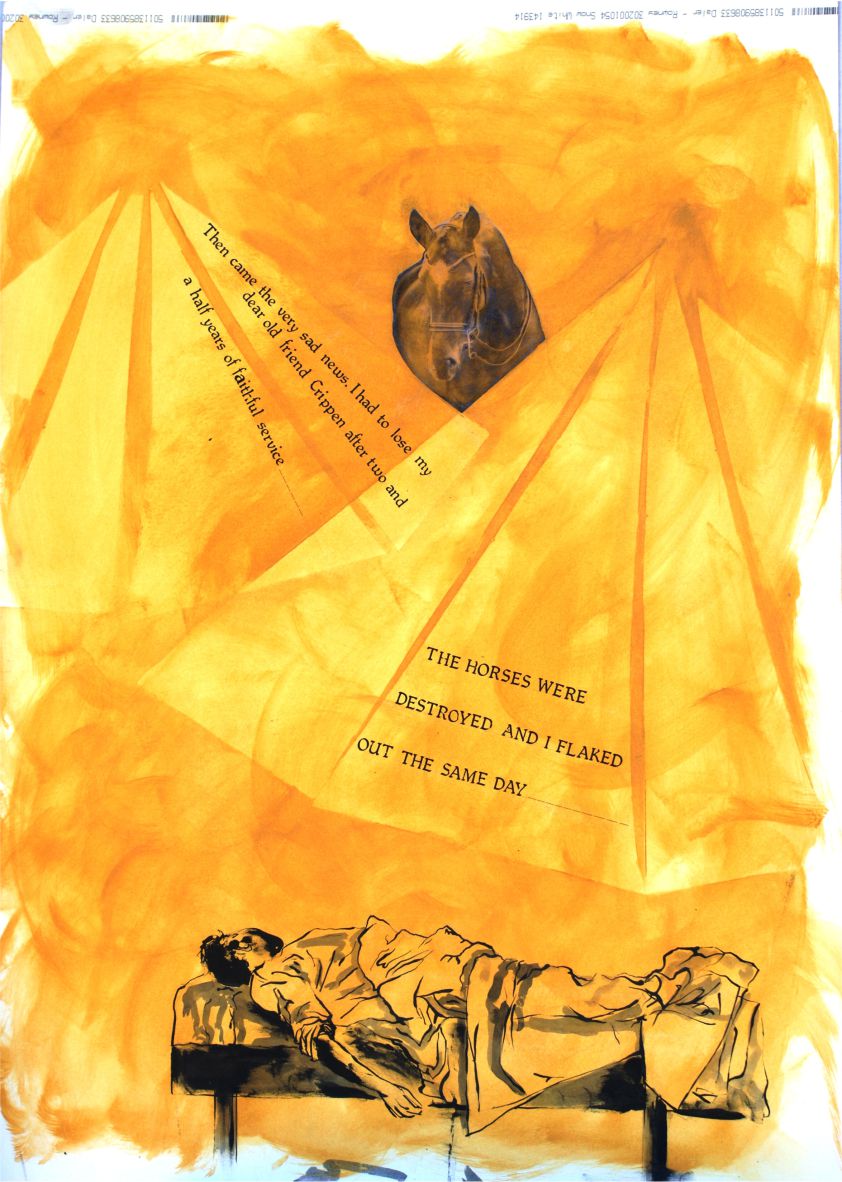

Painting 11. Crippen and Malaria

“Then it was time to feed the horses and look after the inner man. This was done in record time and rations were very soon in evidence, a life saver after those miserable days in the hills and five days awaiting our transport. Unfortunately I had a severe attack of malaria and was confined to my saturated bivouac.”

Here he was visited by Major Bramfield who asked about his condition and gave him bad news about the fate of the horses now that the war was over. Charley’s horse Crippen and another horse were now owned by the widow of Major Winterbottom, his commanding officer. She did not want them back and they were to be destroyed”

“This really hit me badly and I said, “This means that I have to lose my dear old friend Crippen after two and a half years of faithful service.” He replied, “I am very sorry, Garratt, but I am afraid that is so.” The two horses were destroyed and I flaked out the same day and woke up days later in the 63 military hospital in Salonika.”

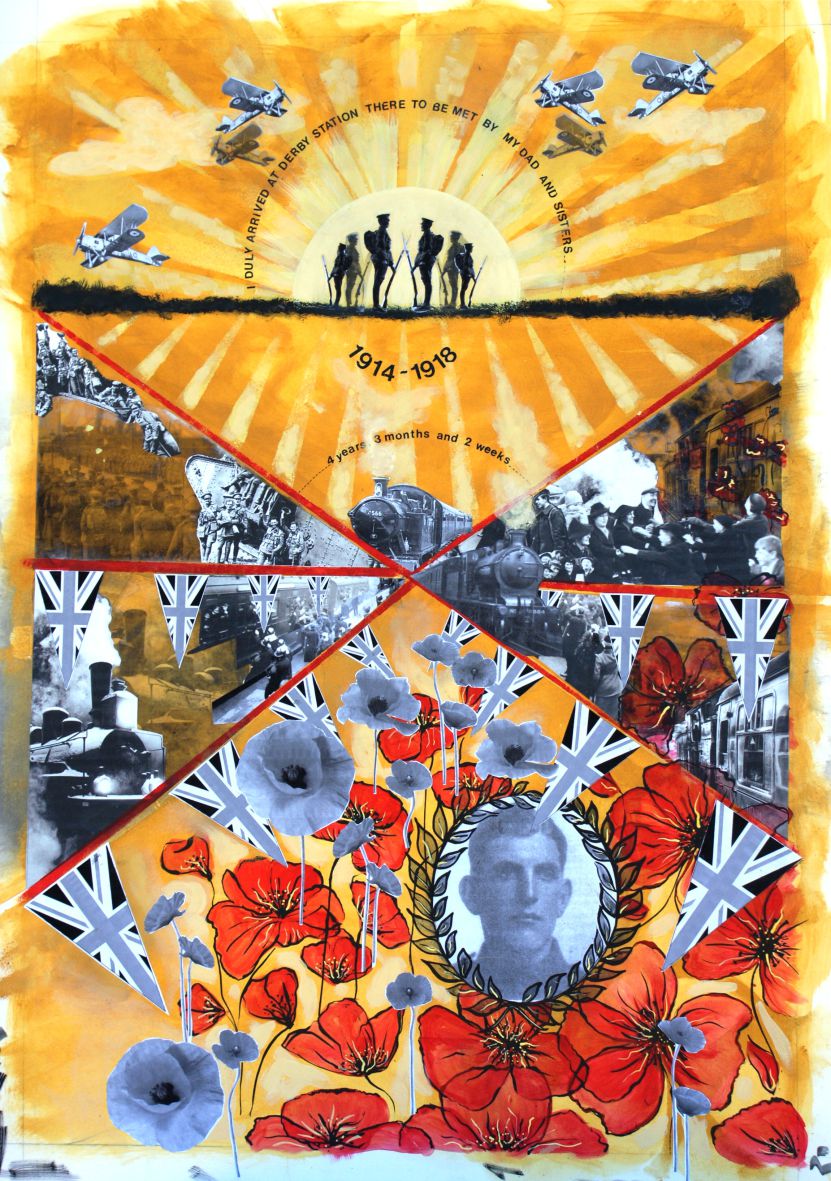

Painting 12. Home at Last

Charley developed pneumonia with the malaria. When he began to make a steady recovery he begged to be sent home and he was discharged in January 1919. He sailed from Salonica to Brindisi.

“ ---- where we remained for a couple of days, then entrained for France. What a journey this turned out to be. Instead of reasonably comfortable railway carriages, we were loaded into rail goods vans, so many men per van. This turned out to be a five day journey cooped up in those stinking vans”

Charley’s health began to deteriorate and he crawled into a look out cabin which was bitterly cold and went to sleep. He was found and came to in a Cherbourg hospital where some days later he had a surprise visit from his parents.

“What a reunion, we hugged and cried and hugged. I do not think I ever saw Dad cry before but he did that day.”

Charley’s parents returned home and he was eventually discharged only to collapse on the ship to England. He was admitted to hospital in Southampton before being finally discharged.

“I duly arrived at Derby station, there to be met by Dad and sisters Amy and Lena. ---------- it’s hard for me to describe the meeting with Mother and Granny Garratt. I remember dear Granny Garratt saying, “God has answered our prayers and has brought you back to us.”